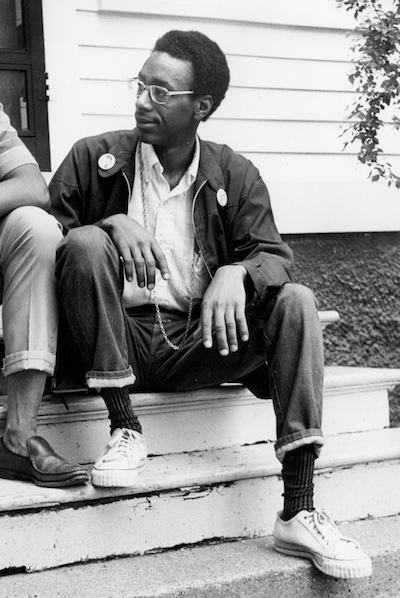

Oral history interview with Frank E. Thomas, class of 1971, conducted by Stuart Yeager.

Oral history interview with Frank E. Thomas, class of 1971, conducted by Stuart Yeager.

Stuart Yeager: I want to start out by reminding you quickly or just reading some things to you of some of the events that took place in 1968‚ when you first came to school here. You did come in 1967‚ well I won't get into the events of 1967 but they were probably many of the same things that were going on in '68. We'll move towards a heightened strength in the tip of the civil rights movement. By 1968‚ by April‚ Martin Luther King was assassinated‚ rioting broke out in U.S. cities all over the country‚ the House passed a bill banning racial discrimination against housing. The medium Negro income was $4‚900 as compared with $8‚000 for a white family. We were in the midst of Vietnam. I want to keep in mind‚ I'm sure you have them in mind‚ I was pretty young at the time. First I'd like to ask you some questions about your family‚ your background and then we'll move into your arrival at Grinnell and talk about some of your experiences. Can you begin by telling me a little bit about where you are from‚ your family background?

Frank Thomas: I was born in Arkansas and my family moved to Chicago‚ fortunately they took me with them‚ when I was three and a half. And I was born in 1944 which I think is going to be somewhat irrelevant to what we're talking about as far as my experience at Grinnell. I grew up in Chicago and went to high school there and later worked. I got out of high school in January of '62. Chicago and some states still ran a split system where you could get out in mid-year. So I got out in January of 1962 and I did not go to college right away. I entered Grinnell as a matter of fact in January of '67. So I was almost 23 when I got there. And I worked for those five years between high school and Grinnell. I was one of three surviving children to my mother. My parents separated for good in 1960. They had had a couple of separations before that and essentially from 1960 until the time that I became an independent supporting person‚ my family was on ADC‚ and that was the family income except for what we supplemented through paper routes or whatever. So I grew up in the south side of Chicago and had‚ I guess in some ways‚ I had a lot more involvement with white people during that time because of the church that I went to. I was involved with a southern integrated church and the people had been coming to that church for a number of years from other places‚ so I think it was some involvement...

Yeager: There was some involvement.

Thomas: So I was essentially a street kid‚ I did not belong to a gang and I did not believe in a gang. I was not a street person in the sense that I belonged to a gang but growing up in the streets of Chicago you have to become a street person to some extent‚ so I was a street person. I worked.

Yeager: What kinds of jobs did you have?

Thomas: I worked as a secretary for a while‚ and that was pretty much right after‚ right after high school because I was very interested in typing when I was young and I became a good typist and I worked as a secretary for a dentist‚ a doctor‚ and part-time for an accountant who had been one of my teachers in high school who ran a business on the side‚ so I typed and did things like that. After that I worked for the Treasury Dept. as a clerk typist for nine months I think it was. At which point I also did a stint as most young black people did during those times in Chicago when most young black people worked in the Post Office. I always went to the Post Office. I did that for long time engagements or for short time engagements. I worked for the Post Office for awhile‚ before I got my job as a clerk typist. Then in late '63‚ in November of ’63‚ I found out that I had TB. I went into the Tuberculosis Sanitarium in Chicago and stayed in there from Nov. of '63 to July of '64 or June‚ I'm never sure about the time but I guess it’s not important‚ because I had a history of asthma; they were not going to operate on me during the time of high allery season‚ and my particular form of TB was resistant to the chemical medication. So they weren't going to operate so I thought‚ “Okay‚ I'll go out and them come back.“ They heard that a lot of times but I did come back.

Yeager: You were very‚ very ill?

Thomas: No‚ I wasn't. I never felt that I had TB‚ I never had any debilitating effects so they tried to keep us calmed down because we were young. And I went in there when I was nineteen‚ and we would do athletic things‚ stuff like that and people were trying to tell us you can't do things like that‚ you're all so sick‚ well what are you talking about. So‚ fortunately I had a small area of my lung that was involved‚ upper left lobe‚ and I went out in July and through my church to summer camp. And went back in October of '64 for my operation. Spent a month in there building up and I had my operation in November of '64. I was released from the hospital‚ from the Sanitarium in January‚ end of December‚ January. And began working for the Tuberculosis Sanitarium‚ not the same one but the one in Hinsdale. Because of a different environment‚ it was all white. All white community‚ in Hinsdale‚ Illinois. And I lived on the grounds. They had housing that they rented cheap to anybody that lived and worked there‚ and started getting interested in going to school at Grinnell. Right after high school I had gotten admitted into some places‚ but I had no money. That was just prior to the big push for getting black students in places. I had been an underachiever in high school. I didn't begin school until I was eight because of my asthma. I went through grade school until I was twelve and a half‚ then went into high school and in retrospect I think that what happened that I sort of burned out because I had a lot of other things going on and I was sort of tired and never had a chance to be a child. So for the first two years‚ I really essentially did not work up to my potential. The indicators were there. People who knew said you have to work up to potential‚ but beginning into my sophmore year just before my junior year I started to work up‚ decided to do something so from then on I did work up to my potential‚ became an “A“ student from that point. That was not enough if I don't get any money. The most I could get was $1‚000 for my student loan at the time. I wasn't getting any scholarship money. Everyone said we'd like to have you be here. I got a look at Dartmouth and places like that but no money. As I said‚ it was just before the big push. So going back to '65 after my TB. I worked for the TB Sanitarium‚ I got interested in school again. And I had already heard about Grinnell‚ and I had already sort of inquired in high school‚ and I read through the catalogs and looking for places nearby Grinnell‚ nearby. But then I moved on to continue working as a laboratory assistant in the TB Sanitarium and went then filling out an application--applied to Arizona State. I had the notion that wanted to become a chemical engineer. And I'm glad I got into that. But Arizona State admitted me‚ and I was all set to go to Arizona State in the fall of '66‚ and that fell through— at the last moment they just ran out of money. That was devastating because I was all set to go‚ and I had been‚ I though I had been committed to money. I'd been orally committed the money. There was nothing on paper. I got a call. That was one of the devastating times of my life. I got a call out of the blue from this woman who was a personal secretary saying I'm sorry we don't have the money. Well‚ I wasn't really aware of some of the kinds of contacts and callers I could utilize to try and push that thing so I didn't do it. And I quite my job at the TB Sanitarium so I suddenly needed a job and a friend of mine‚ a minister who was familiar with a guy who was also an Episcopalian who was his friends he was a manager‚ a retail manager or manager of the regional office of Proctor and Gamble and ran the data processing department. I went down and got a job as computer operator‚ through that connection. And it was there that I was working when Grinnell came into my life once again. That was in the fall of '66. I began in September. A friend of mine that I'd gone through the last year and a half of grade school and all through high school had gone to Harvard‚ and I was corresponding with him

Yeager: Now did you go to a high school in the ghetto area?

Thomas: Yes.

Yeager: And you had some students that really came out of there and emerged to be top students?

Thomas: Yeah‚ I guess I should explain that a little bit. You are familiar with tracking in schools--that you track certain students. Some students are perceived as bright. Some are perceived as average. Some are perceived to be less than average. We were perceived as a group. My entering group in high school; there was a group of us. It was an all black high school incidently. I guess to say it in today's terms‚ it was 99% black‚ but I think we might of had a couple of Hispanics or something like that. We were perceived as a group; there was about twenty-five of us as being the cream within that time‚ and I stayed within that track program even though I was not working up to potential in high school. I stayed within that program the whole time‚ by the grace of God‚ by the fact that people believed‚ that they knew I had it. So we were put in what they called‚ they didn't call it track they called it accellerated program. That had its good points and its bad points. Its bad point for me was that because I had gone through grade school so rapidly and people assumed from these bright people that we had a lot more knowledge than we actually had about certain things. One of the things that they assumed we had knowledge was grammar. We didn't know nothing about English grammar for the most part. We knew a little bit‚ of course‚ we learned some things‚ in terms of the basic kind of things they say to you as a student would have gotten from your home and from school. We didn't. But at home we're not getting English grammar.

Yeager: What type of educational background did you parents have? Did they both finish high school?

Thomas: No‚ I was the first‚ the second in my whole family to finish high school.

Yeager: How far did they get?

Thomas: My mother got to 11th grade and my father got out of high school right after she dropped out. She dropped out‚ she was a hell raiser when she was young. Her sister was the first high school graduate in the family in Arkansas‚ that's where they were from. She had graduated from high school in Arkansas‚ she was the first one. I was the second. My brother--I had an older brother--he was two years older than I was and he had dropped out and later on he went back to finish. So in all of my family; father's side‚ mother's side‚ I was the second high school graduate. So high school was really kind of a strange thing because I was in an accellerated program and we were like just being given a whole bunch of things‚ but no basic skills in a lot of things because people made some assumptions about what we could do and what we knew. That was what exposed something bad but yet exposed a lot of different things‚ that a lot of students were not going to be exposed to but we were also not exposed to basic things. We found that out graphically in 1961‚ in the summer of 1961‚ there was a move to start merging black students in wath certain kinds of programs where more advantaged students were getting into white high schools.

Yeager: Was this in high school?

Thomas: Yeah‚ for the summer. So we went out--a group of us went out for the summer to this white high school to take accelerated programs in English‚ geometry‚ chemistry. There were about four areas in that time. We took English some of us‚ we got wiped‚ we just got wiped; totally blown away. We all survivied of course‚ but it was an experience I would not like to go through again‚ because we thought we were hot shit‚ and we though we really had it. We went out there and sat with white students for the first time as a competitive process and talking about English structure‚ we couldn't make any out. The closest we got to it was the previous English class we had in high school before that summer and the teacher was sort of going a lot of other things‚ but every now and then he'd try and make some stabs at teaching us. But that was a valuable lesson at the time for all of us and then we got out of school in January‚ the following January in '62. In effect then we had this thing going‚ and my friend‚ the Harvard student‚ my friend had been a better predictor. Harvard had tapped him and said we want you to come up at Harvard. Harvard was leading the move to grab people. All of us‚ all of us within that twenty-five group or so—I don't know if that's the exact number‚ but I think it was about twenty-five--all of us were expected to go to college. It was presumed we would all go to college. So he got in time to go to Harvard‚ but Harvard said when they looked at him. They evaluated him. They said‚ “Well‚ we want you to go to a prep school for a year.“ This is after high school. So they sent him to Mt. Herman. So he went to Mt. Herman for a year after high school. And that was a valuable experience both for him and for me because he and I were very close‚ and we wrote and I went out to see him. It was a vicarious experience for me‚ but it was valuable. So Harvard sent him out there to study at Mt‚ Herman so he did that; and he got out of Mt. Herman and went into Harvard '62 through '64. And while he was at Harvard‚ and then when moving up now to '66; when I was suddenly working for Proctor and Gamble as a computer operator. I had gotten some information and applied to Grinnell in that time and had visited Grinnell in March of '66. I just had been working at the TB thing for a year. I had a vacation‚ and I took a ten-day bus ride to Tacoma to see my sister-in-law; my brother was in the service and he's married. So I went out to see her‚ and I had wanted to see that part of the country‚ and on the way I stopped at Grinnell to visit as sort of a prospective. And I liked the campus and I thought it was a nice place. I had applied to Grinnell‚ but I had let that lapse because 1) I had applied to Arizona State and 2) I didn’t really know if I wanted to go to that kind of rich school. I wanted to be a chemical engineer and Arizona State had a good program. Come '66 then‚ late fall of '66‚ I was still without a school‚ and I was working. And I got a letter from my friend which said that‚ “Grinnell is looking for you‚ and to contact John‚ a friend of ours‚ the minister friend.“ So I contacted John‚ and John knew a guy by the name of Harold Hardin. I don't know what class he was‚ but Harold in some way—I never did find out—said‚ “This is where Frank is.“ and I contacted Grinnell. Dale Terry who was director of admissions at the time siad‚ “Where have you been?“ “We’ve been looking for you.“ So I told him what had happened. So we started getting my act together to come to school. And I was going to enter in January of '67.

Well‚ the problem with that was I had gone to a junior college off and on and had taken four courses all together in these intervening years and had dropped three of them because they were below my level; the only one I kept was German. They had a problem getting the transcript from the junior college. We also had a problem getting my medical history. Getting the records from the TB Sanitarium‚ the bureaucracy of it was your problem. Things kept moving along‚ moving along and suddenly in December‚ I finally got the stuff‚ and I'd talked to Dale Terry when we'd finally got the stuff‚ and he said‚ “Well‚ it's going to be too late to get you in January. Well‚ why don't you take the spring and go to a junior college again and keep your brain sharp and enter in September of '67.“ So I said‚ “Okay‚“ But what happened after that was ray friend thad told my friend John what had happened and John siad‚ “Do you still want to go to Grinnell?“ I said‚“Yes.“

Yeager: Had he graduated from Harvard by now?

Thomas: No‚ my friend had‚ not friend was the guy who went to Harvard. He still was at Harvard‚ out John was the minister. So I was talking to him‚ and he said‚ “Do you still want to go?“ And I said‚ “Yes‚“ So I heard nothing more from him and then Thursday‚ January 12th--I can figure by the day because it was the day of the first superbowl that I arrived at Grinnell. What happened was that Thursday John called me‚ and I was home because I had injured my foot--gotten athlete's fungus in a broken blister which eventually ate a hole in my foot. So I was off work and John called me and said‚ “Do you still want to go to Grinnell‚ and I said‚ “Yes.“ He said‚ he'd get back to me. And literally that's the way the conversation went. So I said‚ “Okay‚“ Sunday morning‚ January 15th‚ I got a call about 9:00 in the morning from John‚ and he said‚ “How soon can you get out to Grinnell?“ “I don't know.“ He said‚ “Find out and get back to me.“

So I called around town to the Rock Island‚ used to run a train right through town‚ and they said they could get me out here‚ train left around 2:00 and could get me out here around 8:00 p.m. Well‚ I didn't know anything about Rook Island: I didn't know that eight meant twelve to them. So you get on the train and leave at 2:00 or something like that. Be there at 8:00 and be on it. Sunday‚ I had very little money in my pocket‚ and I had some money in the bank. My family was trying to get a few things ready. So I called Thad’s younger brother with whom I had been friends‚ and the whole family. So he came over and helped and they all got me down to the train station and I was off to Grinnell.

Yeager: Can I ask you a couple more questions? Can you tell me what your parents' occupations were and what their politicaly affiliations were?

Thomas: My mother had done some jobs. My father had been basically a mechanic. He really loved cars. He worked on cars. My mother had some factory jobs‚ but after she went on ADC essentially she did not work. She wasn't allowed to work.

Yeager: How many children did she have?

Thomas: There were three children‚ three of them. Their politcal affiliation. Well‚ they were pretty well‚ apolitical‚ but essentially they were Democrats. That was their party selection.

Yeager: Do you remember them voting? At the time‚ the only reason I'm interested is that at the time that you leaving high school‚ they were having difficulty registering people to vote at all or voting in the South.

Thomas: I don’t remember my father ever voting. My mother voted. I don't ever remember my father voting. And I voted for the first time--you still had to be twenty-one in those days--I woted for the first time in '66.

Yeager: Who did you vote for? Johnson?

Thomas: The first vote I cast was for a state election and was for Charles Percy. I guess by philosophy I was leaning toward Democrat‚ but Percy was saying the right things. So I was twenty-one and I could vote.

Yeager: Who did you vote for in the presidential election? You didn't vote for Goldwater?

Thomas: Oh no‚ no‚ I was never a Republican. I voted for Johnson. I was never a Republican. But my first vote had been cast for an intelligent person. There were Democrats and 1 voted for them too. Percy‚ the Senatorial candidate in Illinois‚ was the better of the two people. I can't remember who ran against Percy. So anyway that was my first vote. I guess we were Democrats.

Yeager: In that campaign if you remember‚ were there issues or questions of race being discussed in the campaign‚ and how were you affected by that?

Thomas: Not in Chicago‚ and there were issues of race‚ and there was the black vote. But Chicago‚ you may have heard has a judicial system all its own. So it didn't really matter. That was clear. They just assigned certain numbers of black votes that they wanted‚ and if the numbers didn't turn out they added them anyway. So it really didn't matter‚ and I took it all very seriously‚ and I was really believing in the American system and that your vote counted and I still do. I still believe in it‚ and I still don't tell people after the election like right now. It is sort of unusual to say that I voted for Percy or Johnson because I really don't tell people. I really bought that whole bit. So it didn't really matter whether there was a question of race. The questions came up later. Like in '68 and things like that. At the time that I started voting that was not a significant issue in Chicago. There was in some places but not in Chicago because it didn't matter. Daley ran things. He wanted this. He wanted that‚ and he got it.

Yeager: Well‚ we kind of got into how you chose Grinnell. What were your friends’ reactions to choosing Grinnell. What were your parents' reactions to choosing Grinnell‚ and do you consider yourself actively recruited because you had these contacts with John.

Thomas: Right‚ right. Well‚ I was actually recruited because John Dreibelbis was interested in me‚ and he knew I had an interest in Grinnell. And he had a friendship with Harold Hardin. So Harold Hardin through John had actually recruited me. The college itself did not‚ but I will say for the college's benefit that the college once I got back in the process was very good. They worked hard with me to get me to come to Grinnell‚ and they were surprised when I showed up on the morning of January 16th. And I got here in the morning about 12:30 of January 16th. John told me to meet the Episcopal minister‚ that he was going to meet me at the railroad station‚ and he was not there. -I called and got another ticket home. So my second view of Grinnell was sort of when I came back that time as opposed to that itme I came in March of '66. I woke up staring into these blue eyes. This little girl was standing there‚ and she went off‚ and said‚ “Mama‚ that man's awake.“ John had told me not to go over to the campus ’till about 10:00‚ that's when they were expecting me. I found out. I got to the campus‚ and I walked in with my crutches‚ and I saw Dale Terry greeting me and asking me how I was doing‚ what was wrong with my foot and that kind of thing. Then he said‚ “Frank‚ what are you doing here?“ I looked at him‚ and 14‚000 wheels suddenly started spinning‚ and I’d suddenly figured out that John had come up with a plan‚ that he knew that Grinnell had accepted me‚ and that I was going to enter in September. He felt that if I did--I think he thought if I didn't go in January that I might lose interest. Well‚ I was not going to lose interest. So he had sent me out to Grinnell on the theory that if I got out here they were not going to send me home. Well‚ I think he was right‚ but it did not seem that way at the time. So they all said‚ “I thought we had agreed‚ and we talked about it.“ They said‚ “Okay‚ I’ll tell you what we're going to do.“ He said what language are you interested in‚ and I said‚ “German and French.“ He said‚ “Which one would you prefer?' I said‚ “German.“ So he gave me an appointment with Professor Brown in the German Department and to go see him and eat lunch and come back after lunch and the financial aid people were meeting this morning‚ and I'll talk with someone about your case and see what we can do for you. I came back affter lunch and came in‚ and Dale said‚ “Well‚ welcome to Grinnell.“ That's how I got in.

Yeager: Were your friends supportive of your going to Grinnell?

Thomas: Yes.

Yeager: Did they think it was unusual that you were going to such a rura1 school or not really?

Thomas: No‚ no not really. Thaddas had gone to Harvard‚ a white school‚ and other people always knew I’d go to college so they were very supportive. They had no problem with me going to college. My mother had some apprehensions about me going out to Iowa with all the white people and going away from home. She didn't know what I was going to do when I got there. But hell‚ I was resisting the idea. I was an adult‚ and I thought it was silly for her to be that concerned about it. But she was kind of concerned that I'd be out there with all those white people‚ and what kind of effect that was going to have on me‚ and she wanted me to know that I could come home if things got bad. But for the most part‚ people were very supportive to this.

Yeager: What were your goals at Grinnell? Your outlook for the future‚ and if any‚ what dreams did you have when you came to Grinnell for the future?

Thomas: My goal at Grinnell was to get that piece of paper‚ and I knew from the things I'd done in that intervening five years‚ I knew‚ my feeling that academics were not that important. What are you looking for?

Yeager: I just want to make sure this tape does not run out. Okay‚ can watch it.

Thomas: Academics‚ per se‚ were not that important as staying in and getting enough grades sufficient to stay in Grinnell. My goal was to get that piece of paper‚ and my secondary goal was to experience fun; have my childhood‚ because I had been forced in growing up to accept a lot of responsibility for family counseling--counseling other persons in my family and doing other things that essentially took my childhood away. I had to be a responsible kid so I had never really had a chance to sort of play. And I saw Grinnell as an opportunity to do that.

Yeager: Had you had time to date while you were in Chicago? I mean you weren't that busy.

Thomas: No‚ I dated. I dated more after high school than I did in high school. Yes‚ I did that kind of stuff. It was just that I had to be responsible for my sister. And it was a battle. I kept fighting getting married. Some of the people that I dated were interested in getting married--particularly‚ this one woman. My family was very‚ filled with pressure to get married. Get married. And eventually we broke up because of the very issue. She wanted to get married now‚ and I said‚ “Look‚ I gotta go to school.“ Those were our continuing battles‚ and she said‚ “Well‚ do it and you can always go here.“ I said that if I got married I knew that I wouldn't go to school. That was one of the serendipitous kinds of decisions I made. So we broke up in '66.

Yeager: Is this someone you were very close to?

Thomas: Oh yes‚ very close. We’d been together since the summer of ’63. So ray goals were to have fun and get the piece of paper. And just sort of experience college life‚ going back to my ideas about buying the “American Dream.“ I had thought that part of the dream was college. That was going to be a very important time of my life. Although somewhat older than the average entering student. I saw that as a time to do that kind of thing. Sc that’s what I did‚ I jokingly refer to the majoring in Grinnell in folk dancing‚ table tennis‚ and women--general recreation. My actual major was history. But I thought for the future‚ I saw myself coming out and actually being a psychologist because I wanted to be a psychologist. Grinnell changed that because Grinnell at the time was what we call the “rat“ school. It was not dealing with people. It did not have the facilities.

Yeager: What kind of a school did you call it? A “rad“ school? A “rat“ school? r.a.t.

Thomas: Yes‚ an experimental‚ with running mice through mazes and things like that.

I was not interested in that. I was people-orientated so I was not interested in that kind of thing. So that changed me into something else. I had to become something so I changed to a history major. And from a history major I wanted to go into Law school. I woke up in the beginning of my senior year‚ end of my junior year; suddenly realized I had a decision to make; and I also had a good CUM in ray major. I was not good overall‚ but I got really essentially plagued‚ and I said what am. I going to do? I can't go to school in history. So I applied to Law school.

Yeager: But you didn't have that goal in mind when you started Grinnell?

Thomas: No‚ absolutely no because my mother wanted me to become a lawyer. She was bound and determined that her younger‚ youngest son was going to be a lawyer. And the older one was going to be a doctor.

Yeager: Did he become a doctor?

Thomas: No. And hell‚ I thought that all that time up until I woke up and said what am I going to do? So I went into Law school. I fullfilled her dream. I became a lawyer. But that was not my dream.

Yeager: What was your ultimate dream? Was it to become a chemical engineer at the time?

Thomas: No‚ I had changed it. Well‚ my ultimate dream at the time when I first began at Grinnell was to be a psychologist. During that time‚ I'm not sure what I was going to do after I realized I was not going to be a psychologist at Grinnell. I guess I didn't have any real vision. I knew I'd get out of school. I knew I'd do something. But I didn't know what I was going to do. I had no worries‚ incidently‚ because I knew that I had a lot of talent and ability‚ and I knew I was going to be something.

Yeager: So you came into the school with some confidence in yourself? That probably had something to do with your work experience? rhat you had the years of independence.

Thomas: I think so. I think that was definitely the basis for that.

Yeager: I was going to ask you what were you primary concerns as a student at Grinnell. Of course‚ that's related to your goals. You wanted to play. You wanted to get your diploma. What were your concerns in the world‚ your concerns‚ your general concerns? What were you thinking about at the time?

Thomas: I was thinking about the fact that the country was in a mess racially. I was very much against the war.

Yeager: Can I interrupt? Your brother was in the service‚ but was he in the war itself?

Thomas: Yes‚ to some extent. Although he doesn’t talk about it‚ and it's something we keep from my mom. She was always worried that he'd go to Vietnam. He did go to Vietnam‚ but he doesn't talk about it. Yes‚ I don’t know what to say‚ but yes he did. So I don't know yet to this day to what extent he did what in Vietnam.

Yeager: He didn't tell you that he'd been in Vietnam?

Thomas: He told me he had been there‚ but he didn't want to discuss the experience‚ and he especially did not want to discuss it with my mother there.

Yeager: Okay‚ so you were very much against the war.

Thomas: And I was that the political process in this country was going nowhere. That it did not speak to the needs‚ that I saw in this country‚ for quality‚ for the end of the war‚ for getting rid of the crap‚ for providing some means for people to live decent‚ productive lives. I thought the political process was not speaking for those needs. I guess for my age‚ I was also affected very much by John. Kennedy in that I thought Kennedy as being as not as good as a lot of people saw him‚ but I saw him as being sort of a symbol. And I think there's a true lesson in that because he really was a symbol for a lot of people.

Yeager: What did he symbolize to you?

Thomas: Spirit. He symbolized an awakening of a different kind of American spirit. A spirit where a lot of people could pull together instead of a lot of poepl getting it and being supported by a lot of people like myself; black people‚ people in the lower economic scale‚ whatever. And that he gave a lot of hope to a lot of people. He was a symbol. Although he‚ himself‚ I recognized the fact that John Kennedy‚ himself‚ really was not that much of a good person‚ in the sense that we sort of saw him and idolized him from afar. As a person he wasn't that way but as a symbol he was that way and of course‚ maybe that was in a way more important thing‚ as he was perceived. I thought of John F. Kennedy in that way. So that affected me. So I guess sort of important to that perception of John F. Kennedy‚ and I recognized that I was anti-Nixon. I had been antiNixon since 1952 just before I turned eight. I heard Nixon on the radio‚ and I said to my mother‚ and I remember very distinctively‚ “I don't like that man.“ I did not like him‚ and I still don't like Nixon. So there he was‚ running against this guy who was going to symbolize things. And then Kennedy was killed‚ and Nixon went on being wierd and other things. So Johnson had my sight because Johnson rode the grounds well for the Kennedy staff...

Yeager: After Kennedy's death...

Thomas: ...to institute a lot of things which on the balance were very good. There's a lot of debate with sociologists and historians as to whether there was any good for society as a whole. At the time‚ I still think so because I think that may have created certain problems. But those problems may have been created more because of the fact‚ people at the top really got greedy. And a lot of people got greedy‚ putting their fingers into the pie. But the basic concept of a freedom society in providing equal opportunities‚ voting rights‚ all that kind of stuff were very good for the society and I still think they were.

Yeager: There was a question of monitoring. You know trying to put some type of control and watch over things to make sure they ran efficiently. The ideas themself were accurate for the times‚ but right now?

Thomas: But of course‚ during this time the marches were going. I went on a march. I met Dr. King; I marched with Dr. King.

Yeager: You marched with Dr. King? Where?

Thomas: In Chicago. I didn't get that close to him‚ but nevertheless I marched with Dr. King.

Yeager: His daughter is here now. You know all that.

Thomas: And Dr. King still affected me. I was in the King camp‚ and it's something that's not talked about that much anymore‚ but just before Dr. King was killed there was a big split in the black community as to whether King was on the right track. King had suddenly gone into being against the war. There was a logical extension as to who the man was and the kind of things he was saying. So he had gone to being against the war‚ and some of the people; the black militants were saying at the time‚ “Hey‚ we are still here in this country being hurt‚ and you're not addressing our needs and you are on the wrong track.“; and by then we had various languages or rhetoric coming out of Malcom X and his staff and other people Elijah Muhammed and all these people. All these things were sort of coalescing at one time particularily on people of my generation. So there was a split and my generation really personified that in that those of us that were around my age were splitting as to whether King was on the right track. Were we supposed to follow King or go out and burn building? And all of that got changed in April of '68 when King got killed.

Yeager: I'm going to ask you some mere specific questions about King later. I wanted to know. You said you did not have a problem with adjusting to a rural setting. Is that true? Being brought up in a city as Chicago‚ as cosmopolitan.

Thomas: The only adjustment process I had to a rural setting was that I was already twenty-two when I got here‚ and I had been used to going out and spending until 4:00 a.m. drinking and playing around. When I got to Grinnell‚ women were still being locked up; 10:30 weeknights‚ 11:30 p.m. Friday night‚ 12:30 p.m. on Saturday nights. Although men were not‚ and the bars closed 1:00 a‚m. during the week and 2:00 a.m. on Saturday night. That was the biggest adjustment I had to make to a rural setting. I was old enough and was self contained enough to be able to exist within this place and to recognize the diversity of the things that were being offered that I could take advantage of. So I've never had that kind of sense of aloneness that I think other black students had actually the ones on campus. One thing I had was a lot of contact with white people already. I’d worked in the work-day world within the white world‚ not in the sense of menial jobs where a lot of blacks work; work in a world of white collar area with computers and stuff like that and a lot of people I worked with were fun. So I did not have that sense of alienation although I had a lot of quirks about it at the time I had that kind of thing but not the same feeling. I was sitting here being very much comfortable in Grinnell‚ at the college. I was not that comfortable in town‚ but there were some certain elements in the town. Although I think that on the balance I was more comfortable with the people in town than a lot of other black students were. I think maybe because of the work experience‚ and I was also still an Episcopalian and still active in church and I got involved with still some more people in that town that way; just understand not completely‚ but I had just started growing away from the church‚ but I was still involved with the church.

Yeager: How many black students were attending Grinnell when you arriveq‚ approximately?

Thomas: I would say approximately twenty.

Yeager: Only twenty black students.

Thomas: There might have been thirty.

Yeager: In 1967.

Thomas: There were not a whole lot‚ maybe even less than that. It was a small group‚ and we all got to know each other‚ we all got to know who each other was. So it was small‚ and there was no sense of banding together at the time‚ and as I said before‚ that you would hear from these people who were here at this time that the banding together came about because all these things were happening to the black students‚ within the town especially.

Yeager: That was 1968.

Thomas: 1967-1968.

Yeager: So you were here when the banding began?

Thomas: Oh‚ yeah. I was one of the students here who helped found CBS. See‚ CBS was formed the fall of '67‚ in essence the group began in the early part of '68. So CBS was a functioning entity. I think of it such when King was killed. Fortunately‚ I think fortunately.

Yeager: Was the reaction to King's assassination more than the town's reaction?

Thomas: No‚ it was already there‚ and fortunately it was there when King was assassinated because I think that right before CBS existed things could have been a lot more violent or a lot more things when Kings was killed. So I think it was fortunate that we had CBS‚ but CBS had been formed as a response to what was happening in town. As in the Grinnell black student I think at the time except for the things that were happening in town we were sort of caught here as a groupp some of us that had left their backgrounds. But as a group we wer8 sort of isolated from the surrounding events of the world. There was really an isolated thing.

Yeager: You felt isolated from the world. Did you follow things on the television or through the newspapers?

Thomas: I followed things.

Yeager: You did.

Thomas: Even though‚ a lot of people followed things‚ but in a sense none of that stuff was touching us because Grinnell stayed the same. You were here‚ and stayed the same; the tovm stayed the same. It was only because people started getting beat up and things like that‚ and then we started connecting those events to things that were going on outside the college‚ ahd the need to band together for defensive purposes became a necessity and became a reality.

Yeager: You did address my next question I think. What kind of inter-action did you have with other black students? Was it mostly social or would you say political‚ or both? Or was it different in different years?

Thomas: It was different in different years. Somethimes it was more social‚ and it was also black students‚ or my perception of it was that you socialize with black students mainly in a smaller level.. And it still may be true. I don't know. In smaller levels than you did say as what is perceived now that all the black students are together as a unified whole. We were sort of together as a unified whole but each of us socialized within small cell-type. That's what we did--three or four people in a group socialized. And most of us had a number of white student friends‚ but we spent more time with black friends.

Yeager: Had you had white friends before you came to Grinnell?

Thomas: Yes. That was not a new experience for me.

Yeager: But your closest friends were black‚ or not?

Thomas: My closest were black.

Yeager: Did you have any white roommates‚ Did you have black roommates? Were you in a single?

Thomas: Yes and no. When I came‚ I came in mid-year. I was put into a two-room suite which became the RA suite in Cowle’s Hall and that was the room that was available. I had the room that had the bathroom. There were two guys sharing the other part of the room. So that’s where I lived. Then I stayed in Cowles the following year in '67 through '68‚ and I had then an adjoining room with a guy I had met who was a white guy. had a single room with a connecting door‚ and we became friendly. He was a senior.

Yeager: What was his name?

Thomas: Phil Jones. I had met these people when I was here in '67 and he played table tennis and bridge. Ke taught me bridge. I became very friendly so we roomed next to each other and shared a lot of things. But in that sense I never had a roommate at Grinnell.

Yeager: That was through your whole four years in the same dorm?

Thomas: That's right. I never had a roommate.

Yeager: That's interesting.

Thomas: But I didn't stay in Cowles the whole time. After Cowles‚ I stayed in Cowles a year and a half. After Cowles then I moved to--let's see. From the fall of '68 through '69‚ I stayed in the first coed dorm in Younkers that year. That was also the beginning of the student advisory system. Then I went to the German House the fall of ’69 through the '70’s. And then I got married‚ and we lived off-campus‚ then in an apartment‚ and my wife had come in September of '67 so she still had to finish up.

Yeager: You got married.

Thomas: In '70‚

Yeager: Right after you went to school. How did you know this person?

Thomas: I met her here. I got married in ’70. I met a student who was also class of ’71. and we got married in August of '70‚ and spent the last year here while I had a semester to go‚ and she had a year to go.

Yeager: What is her name?

Thomas: Sheena Brown; Sheena.

Yeager: She was class of '71 also. She didn't come to the conference?

Thomas: She is white. She's not black.

Yeager: Oh‚ I'm sorry. She still could have come to the conference.

Thomas: She had other things to do so she couldn't come.

Yeager: I was going to say did you have any adjustment periods to go through with a white roommate‚ but really didn't have a white roommate‚ and you had experiences in the working world so you didn't have... How did white students generally react to black students?

Thomas: Diverse ways. Depending on the amount of experience. There were; I guess there was a big difference. I think white women acted differently than white men. There were a number of white women in those earlier years who also looked upon the college as a time to play‚ everybody sort of. Those were college years. One of the things they had a chance to do was to date some black men for the first time.

Yeager: What kind of a scale was this dating black males?

Thomas: I think most of the black males on campus at one time or another dated a white woman. Some of us dated more than one. That caused a lot of problems of course being a black community. There was very little of black women dating white‚ men. There were‚ only a couple. So there was sort of a peculiarity effect among some of the white women to go and date a black man fox' the first time. You know what it was like. You know you got some questions from somebody who hasn't been around black people like‚ you know‚ mainly‚ “What's it like growing up black?“ Not the kind of serious typical questions like‚ “Can I feel your hair?“ or “Do you have tails?“ But just trying to find out what it is like. You know. I don’t know‚ what can I try and find out about you to help me understand what's going on in the country. And there were a few‚ as there are in any kind of society of people just wanted to do it because of the status.

Yeager: The Myth.

Thomas: This is where it’s at. I don't know to what extent other people's motives existed for dating a white woman in a black community. My perception of black women on whether or not they were dating a white man. There were several reasons. The main two: They did not find white men as a whole attractive‚ and two‚ they‚ black women as a group‚ I think perceive white males as enemies much more so than black men perceive white women that way So it was difficult to get over those kinds of concepts to date somebody who was white.

Yeager: Had you had any inter-racial dating before you came to Grinnell?

Thomas: One.

Yeager: One‚ so it was not new‚ but yet new to you also?

Thomas: Right.

Yeager: Getting back to the question‚ were you aware of the activities going on outside of Grinnell--national events of Mr. King‚ Malcom X and others?

What about some of the other black people in the town‚ white people too?

Thomas: The people I tended to associate with were interested in those things. I tended to associate with however those white students who had interest in those kinds of things that were going on. And black students as well. I think all the black students for the most part except for the exception of a couple of people‚ were aware of these kinds of events. But I think as a whole all of us were still caught up in that system that none of it was really touching us so until people started getting beat up in town and King got killed‚ but it was all happening out there. There was no sense until King got killed that anybody was going to take over the Forum‚ take over Burling‚ do any of that stuff. That just doesn't happen at Grinnell. We just talk it out. I'm sure that still exists around here that you can always sit around and somebody will say‚ “Well‚ hell‚ Grinnell will talk anything to death.“ And that was the sense. That Grinnell will talk anything to death so you don't take over buildings‚ you don't do something like that. That happens‚ those crazy people out there in Cornell taking some. Not at Grinnell‚ so we were not effectively touched.

Yeager: How do you view? I was going to ask you how you viewed King's and Malcolm X's activities. You said you were in King's camp. What did you like about King and what didn't you like about Malcolm X?

Thomas: I felt that Malcolm X‚ I'll start with Malcolm first. Malcolm X was unnecessary bombastic in some of the things he said. I came to change my view of Malcolm X later as he changed his own to an extent and also I decided that once Malcolm was killed that I had a duty to try and understand Malcclm a little more. And I think that had the effect. King and I were closer because I felt at the time that I had a lot of leanings towards nonviolence and towards change through inter-action into trying to convince people that what they are doing is crazy and then‚ but where our party was King to some extent that some people I was willing to write off and hell. I'm just not going to do it. I’m just not going to do it. I'm just writing you off. You're just a confirmed whatever and that’s it. Whereas King‚ to his credit‚ refused to write those people off publically. I don’t know if he did privately‚ no one knows‚ maybe Coretta. But publically he never wrote anyone off and I think that was important to me because he was really living. I had been very affected by reading about people like Ghandi‚ and people who did these kinds of things in the past years‚ and the fact that I saw King as a Ghandi-like person in that he went through a whole bunch of things on behalf of his people whan at any thousand times he could have said‚ “Hey‚ I'm not going to do this. I'm tired of getting my head beaten. I'm tired of everything.“ But he just kept doing it. He did not have to get involved with the garbage strike. He did not have to get involved with the war‚ but he saw it as a logical extension of who he was and his own kind of theology and his own kind of Christian committment. And that was very important to me because I was still involved with the church in terms of the overall view of the church that was the Christian sense that people could have. I still have that. I still consider myself a Christian‚ but I don’t go near a church anymore because 1 decided that institution was no good. But King did things for me because he was there living that Christian view to the best of sense that one could given the kinds of things that were going on. He was not a saint. And a lot qf people kept saying‚ “be a saint‚ King‚“ or “be a devil.“ And I kept thinking‚ “Hell‚ let the man be a man. He is a Christian‚ and he is telling you what to do and he's doing it.“

Yeager: What were your opinions of the Black Panthers? Did you know of them? I'm sure you were aware of the Black Panthers.

Thomas: Admiration‚ to some extent because I had‚ because of the kinds of responsibility I had had earlier. I had learned to sort of be quiet about expressing certain kinds of opinions. I was a facilitator‚ a mediator rather than a confrontor. So it was sort of an admiration of the Black Panthers‚ those guys were confrontive‚ man! We had a group from Des Moines come down and they sat right here in this room and they were sitting there‚ and they were just going through the thing and one time this cat said‚ “Well we're just here to tell you that stick ’em up motherfucker we came to get ours.“ Thats the kind of things I would not say‚ but it was very influencing. I thought the Panthers were -a good group in the sense I thought they were necessary. The kind of people who were involved with the Panthers except on an individual basis that I would‚ have known this person before‚ I would not insult someone else that was a Panther‚ but if someone were to become a Panther that I had known I would not put that person down. That was just my kind of personality status. I don't enjoy confrontations. And the people who were sort of doing that had really confrontive personalities so I would not willingly insult that person. I thought that they were necessary and I thought they were doing good things in the sense that they provided an edge that a lot of people could not--an effective kind of counter-point to King and to Elijah Muhammed and for me the three of them; three of them as the three movements‚ the three of them provided the effective force at that time to really do things. That was a little gap in there where I perceived myself and some others being‚ that we were the ones who had to sort bridge those gaps between those three. So we were sort of bridging‚ that's the way I felt ourselves at the time‚ as sort of mediators.

Yeager: Did you consider going down South during this period SNCC's activities were going on and some of the...

Thomas: I'd considered it‚ but never did it.

Yeager: There were Grinnell students involved in freedom rides and activities such as that. What were your opinions of those things? What were some of the opinions of the black students of white involvement in civil rights?

Thomas: It changed. My view didn't change. I thought if people wanted to do that it was fine. It was not the kind of thing I was going to do. I'd done my march in Chicago‚ and I'd felt bad about it. I guess that's the closest‚ other than King's assassination‚ that I ever got to being angry about the black experience and things like that. Marching was necessary and was a good thing and all that‚ but I felt frustrated doing it. I felt frustrated within the sort of non-violent Christian response to the marchers being spit upon‚ getting things hurled at you and you would not respond. Although I thought it was necessary. That was the closest that I got to anger‚ during that time. I could get angry individually at some particular person about something‚ but use that to try and facilitate around it or whatever. I was upset about the fact that people were going on riots and things like that and my surmise is that one is that is necessary for some people to do it‚ not just to do it and to come back to those black communities within which they have been accepted but to go back to their own white communities and spread that word. Which a lot of these were not doing. They were going on those rides and then refusing to go back to their own communities and do it. They go home‚ and the whole thing would be like‚ “I do not want to talk about this with my parents‚ my friends or friends of my parents.“

Yeager: Which defeated the whole purpose because this is what they were trying to reach; the power of the country. I want to know whether you were involved in international activities at Grinnell? I've been studying the ealy history of blacks at Grinnell in the 20th century. Many of the early students even though they were American were involved in what they call the Cosmopolitan Club. It was one of the few outlets for black students in those days. They didn't have the CBS. The 60's was the time of international unrest for many African countries‚ Ghana. It may have been in '62. There were other African countries following.

Thomas: I had a slightly different view about that. I was very much concerned and still am‚ about what happens in Africa‚ particularily Africa. I’ve also had some concern about what happens in South America. I think that black people for instance‚ have a‚ lot more empathy towards some of the people in South America then we realize. What I saw‚ I disagreed with the African movement. I was born in the U.S. Most of these people were born in the U.S. I knew enough from reading that and had known enough Africans‚ for instance to recognize what was being said by all those people‚ were saying‚ “Hey‚ you didn't come from Africa. You didn't come from here.“ “Get your own house in order and them come visit us and help us and until then we’re going to keep on with the struggle that we got.“ I didn't believe in this system of let's become African‚ let's become this and that. I kind of like some of those things that happened‚ Afro haircuts and all that kind of stuff‚ but accepting the idea of just going to Africa‚ I did not‚ I thought that it was foolishness I though that we had too many problems here to be wasting our energy going to Africa‚ If you want to visit‚ fine. But to say I'm going to move to Africa. I'm going to try and make the U.S. a little Africa whatever that is‚ doesn't make sense.

Yeager: Can I ask‚ were you a member of any major racial organization‚ NAACP‚ National Urban League‚ SNCC?

Thomas: Yes. I was a member of the NAACP‚ but I'm not necessarily a group member of the NAACP now.

Yeager: You're no longer a member now?

Thomas: I'm no longer a member. right. I decided to let it lapse at the time‚ after Grinnell. I guess I was too poor to keep ... I've been since considering becoming a member again. That was the only organization of that kind that I belonged to.

Yeager: Can you tell me‚ were you happy at Grinnell? What did you like most about Grinnell? What did you hate most about Grinnell?

Thomas: I was happy at Grinnell. I guess the thing I disliked most about Grinnell was the sense that was contained within the overall campus community for a freshman to come in‚ that those people who were my peers had things that I did not have. I was sitting in an humanities class with people who had been to Greece‚ who had been to France‚ that kind of thing. I guess Grinnell gave a lot of comfort and cover to people and you can’t tell somebody's a millionaire's daughter or whatever. That's not true cause you can do that. And it definitely became disturbing when they were talking about when they had been to Greece or something. I haven't been to Greece. That's what I disliked‚ and the second thing I disliked at Grinnell although I am kind of not so concerned about it now. I found the tendency to over-intellectualize. I don't know if they use that phrase. In the sense that people just talked things to death. They would put intellectual connotations in things that didn't deal with reality.

Yeager: What did you love most about Grinnell?

Thomas: Intellectual stimulation. It sounds contradictory but‚ I liked intellectual stimulation. I liked the opportunity to experience all these cultural events free‚ to meet all these kinds of people‚ and I liked most meeting some of these people who became friends throughout this time.

Yeager: Have you kept friends since then? You have several friends at Grinnell that you have kept in contact with?

Thomas: Yes. White and black. Lots of them.

Yeager: One question aside and you can go back to the conference. Had you heard of A. Philip Randolph’s activities or was that too early for you? I know he continued up to ’63 but he really wasn't in the limelight that much.

Thomas: Yes‚ I had heard about A. Philip Randolph.

Yeager: You weren't particularily interested in the man? He didn't affect you. He wasn’t one of the more captivating leaders and‚ he certainly had a major role in the forties. You were born in the forties?

Thomas: Yes‚ I was born in ’44. No‚ he didn't have a major visible role. Of course‚ he had some affect‚ but no he really didn't.

- Title:

- Oral history interview with Frank E. Thomas, class of 1971, conducted by Stuart Yeager.

- Creator:

- Yeager, Stuart

- Date Created:

- 1971

- Description:

- An oral history interview with Frank E. Thomas. Thomas is a member of the class of 1971. Two original parts merged to one. Recorded on September 12th, 1981

- Subjects:

- Black Experience at Grinnell College Concerned Black Students National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

- People:

- Thomas, Frank E. Yeager, Stuart Dreibelnis, John Hardin, Harold Brown, Sheena

- Location:

- Grinnell, IA; Chicago, IL

- Source:

- Grinnell College

- Object ID:

- dg_1724967457

- Type:

- Audio Recording

- Format:

- mp3

- Preferred Citation:

- "Oral history interview with Frank E. Thomas, class of 1971, conducted by Stuart Yeager.", The Black Experience at Grinnell College Through Collected Oral History and Documents, 1863–1954, Grinnell College Libraries

- Reference Link:

- https://yeager-collection.grinnell.edu/items/dg_1724967457.html

- Rights:

- Copyright to this work is held by the author(s), in accordance with United States copyright law (USC 17). Readers of this work have certain rights as defined by the law, including but not limited to fair use (17 USC 107 et seq.).