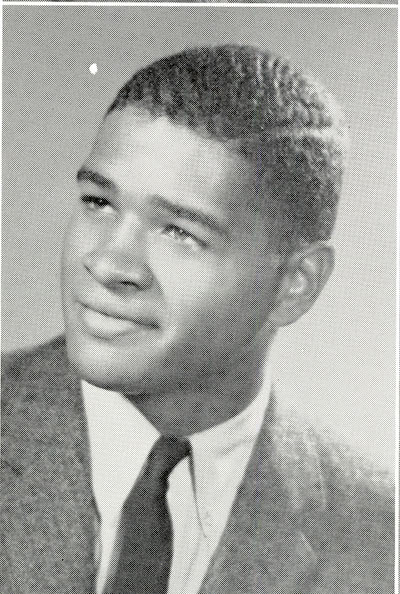

Oral history interview with James Lowry, class of 1961, conducted by Stuart Yeager.

Oral history interview with James Lowry, class of 1961, conducted by Stuart Yeager.

Stuart Yeager: We're going to start by asking you a couple of questions about your parents' occupations and their educational background and your home town. Why don't we start with your parents' occupations?

James Lowry: Both my parents are postal workers‚ and I was born and raised in Chicago‚ Illinois.

Yeager: Can you tell me a little bit about their educational background?

Lowry: High school graduates. Both were high school graduates in Chicago.

Yeager: And they were both from Chicago originally?

Lowry: No‚ from the South. My father's from Tennessee and my mother's from Mississippi.

Yeager: They met in Chicago?

Lowry: They met in Chicago.

Yeager: Do you have any idea when they came from the South to Chicago?

Lowry: Yes. When they both were in their teens.

Yeager: Can you tell me something about your neighborhood in Chicago? Was it segregated? Desegregated?

Lowry: Segregated. Lower middle class‚ I would say.

Yeager: Your high school?

Lowry: Francis Parker.

Yeager: Can you tell me a little bit about the connection between Grinnell and Francis Parker? We have a whole lot of people from Francis Parker.

Lowry: Well‚ I think it's just...if you know anything about Francis Parker‚ Francis Parker is a day school where they spend a lot of emphasis on where students are to go. At one time when I was there‚ it was estimated that the principal spent thirty to forty percent of his time trying to place Francis Parker students in the college or university of their choices‚ and it was just very tough. It was a tough school. I think the other thing was that they tried to fine tune the selection to the personalities‚ and that's why I came here-it was decided. It was almost like a computer.

Yeager: They told you that you were Grinnell material?

Lowry: They told me. Yes. They really‚ they gave us a choice they gave me a choice of about four schools: basically Lawrence‚ Grinnell‚ Kenyon and Oberlin. I visited three of the four-and one twice. And I just decided to go to Grinnell.

Yeager: A few more questions and then we're going to get to Grinnell. Your parents' religious affiliations and their political affiliations?

Lowry: They were Democrats‚ Lutheran.

Yeager: How important was politics in your family?

Lowry: Not very.

Yeager: It was not discussed a lot?

Lowry: No‚ not to a great-great extent.

Yeager: You discussed a little bit how you chose Grinnell? What were some of the reactions your parents had and your friends had to your going to Grinnell?

Lowry: Well‚ in my case‚ my brother had gone to Kenyon‚ so my brother was four years older. And so it wasn't as unique a selection because of my brother. In fact‚ my father wanted me to go to Kenyon‚ because my brother had a very illustrious career at Kenyon. But it was an all-boys school‚ and I really didn't what to go to an all-boys school. And probably didn't want to follow my brother. But they were very used to a liberal arts college‚ so it was not a big shock.

Yeager: Why a small liberal arts college as opposed to a university?

Lowry: I was very interested in athletics.

Yeager: And you thought you'd get better attention in a small school?

Lowry: No‚ I wanted to participate in three sports. I figured could have played one sport in a major university‚ but I couldn't have played all three.

Yeager: Were you recruited by the college?

Lowry: In the typical Grinnell fashion. No‚ I think we kind of showed up at Grinnell's doorstep. Once we showed up-we meaning Jimmy Simmons and myself-we presented ourselves with our credentials and our board scores and athletic prowess‚ then Grinnell got very interested. But it was not a case where Grinnell said‚ “We want you to come here.“

Yeager: So at that time Grinnell wasn't-at the time was making an active effort to recruit black students?

Lowry: No‚ not really. No.

Yeager: Now‚ Allison Davis came a year later?

Lowry: No. We're all roommates. Allison Davis‚ Jimmy Simmons and myself were roommates in Smith Hall.

Yeager: All three came to the doors at the same time.

Lowry: Yes. But they didn't even know Allison was black.

Yeager: What personal and occupational goals did you set for yourself once you arrived there?

Lowry: At that time I thought I wanted to be a lawyer.

Yeager: Any other goals that you set?

Lowry: Not really. It was ...I don't know why‚ when I look back on it‚ but I really didn't have any career goals. I think that's probably common for a lot of blacks around that era. We were here‚ and this was just the first step‚ going to a good school. And I think we thought‚ you know‚ in terms of professional school‚ but in terms of career‚ no. We were just out there.

Yeager: What was your brother doing?

Lowry: My brother‚ this is an example. My brother left Kenyon and went into the Air Force. That was time when R.O.T.C. was almost in most of the schools. And he was in the service for three years-I think three years-and wh~n he came cut‚ he taught at Francis Parker. He was a coach at Francis Parker. He couldn't get a job.

Yeager: He went to school there too‚ right?

Lowry: Yes. And when he applied at several major corporations he couldn't get a job. And so Francis Parker gave him a job.

Yeager: He's not working there still‚ is he?

Lowry: No‚ I guess about two years later‚ after coaching at Francis Parker for two years‚ he then went into an executive training program at Inland Steel in Chicago.

Yeager: So what were your primary concerns as a student?

Lowry: Making it. Surviving. And trying to have fun.

Yeager: I've found that students were much more concerned the four students I've talked to from the fifties-were much more concerned with having a good time‚ as much as today.

Lowry: Yes. Oh yes. We enjoyed it-I think that's why we have a great allegiance. We really-all three of us-Jimmy‚ Allison and myself-really enjoyed our four years‚ It was a lot of fun.

Yeager: You guys were all together. Were you all close friends at Francis Parker?

Lowry: Yes. Allison didn't go to Francis Parker. His brother went there‚ but he didn't go. But we knew each other‚ We've known each other all of our lives.

Yeager: So when you got to Grinnell‚ it was just kind of like an extension of your past experiences.

Lowry: Yes.

Yeager: Can you tell me about some of the activities that all three of you were involved in?

Lowry: Well‚ actually‚ there was kind of a separation. Jimmy and I were very close in both social and athletic areas. Jimmy and I played-our freshman year we both played football‚ basketball and baseball. And then the following three years we both played football and basketball‚ and then he ran track and I played baseball. Allison was not an athlete. He was what they would call a “jag‚“ He was into a lot of stuff. He was into Mortar Board‚ he was into a lot d5f things. But he was not athletically inclined.

Yeager: So the relationship with Allison was more of an academic relationship?

Lowry: Academic and social. We just were three good social friends.

Yeager: Can you tell me a little bit about your dorm life?

Lowry: Well‚ at that time‚ you know‚ the dorm system was different. It was sort of like a fraternity‚ and I thought that that was a very strong thing on campus‚ and probably should have been continued‚ I would think. But Smith Hall was considered the dorm‚ we had the largest share of jocks‚ and the had the highest grade average. We were the dorm‚ scholar athletic and that kind of stuff.

Yeager: Now you were-were you the head of Smith?

Lowry: No‚ Jimmy was.

Yeager: How was the adjustment coming from an urban environment to a rural environment?

Lowry: I loved it.

Yeager: No problems at all.

Lowry: Yeah‚ we had small problems‚ but they were-I mean‚ it was the time. The sixties was‚ the fifties and sixties were not tough times‚ it was just kind of an “up“ period‚ and although they were-there sit-ins and freedom bus rides‚ that was really “down there“ and it was just starting. This was the integrationist period and everybody was trying to lean over backwards to let us know that they wanted us on the campus. And then the fact that we were athletes‚ you know‚ getting B averages‚ kind of enhanced our image. So‚ it was a very good life‚ and even off-campus we were king of looked up to by town people except for the lower class element. And so‚ we didn't really have any problems. We were lonely. Freshman year we were lonely‚ I think neither Jimmy or I dated for the most part of our freshman year. So I think that was tough. It was a social adjustment in terms of social life. We dated the few blacks who were on campus‚ but we didn't date a lot.

Yeager: Was it taboo at that time to date inter-racially?

Lowry: Well‚ I think it was a combination of we were very guarded as trailblazers‚ and we knew our role‚ and we played it and we didn't want to upset the apple cart. That was one thing. I think that other was that you just had a feeling thatI mean‚ there's a sixth sense that we developed that there's certain girls that you could be friendly with‚ but they wouldn't go out with you. So why embarrass them and embarrass yourself? There was a vast percentage of that. It was liberal but not that liberal. Grinnell was not that liberal.

Yeager: You were talking about roles. You said you “played the role.“ Did you feel that you had to play the role?

Lowry: Oh‚ yeah.

Yeager: Why? Why did you feel that at that time?

Lowry: We-you know‚ I just finished a report that I talked about this. It's something you sense. It's a certain sensitivity that blacks have‚ that they have had to have to survive. And it was not really articulated. No one really came out and said‚ “That's the role you have to play.“ But we knew damn well that was the role that was expected of us‚ and we were rewarded for playing that role.

Yeager: So what was the role-specifically?

Lowry: The role-I could take-the worst in a way‚ and that would be just “good‚ happy niggers.“

Yeager: And that's what you wanted to portray?

Lowry: Yes. We were just good‚ happy niggers who bounced the ball and brought glory to Grinnell and everybody loved us and they said‚ “Oh‚ God‚ what can the world be like‚ with these niggers.“ A lot of smiling‚ grinning‚ yeah... and you saw discrimination‚ you saw... And you know‚ every now and then- I didn't take anything-I would set people straight if they'd tell evil coon jokes and stuff like that. So they didn't get away with that. We were big enough‚ so I'm sure a lot of stuff that didn't happen to us might have happened to some more blacks. The other blacks kind of rolled with it. But you just knew‚ you knew what they were expecting‚ you knew what the fashion was.

Yeager: So it was important then that you were all roommates because at least you could relax together. How many other blacks were attending Grinnell?“

Lowry: Yes. good anecdote. You want to anecdote on that? This would be a Have you interviewed Don Stewart yet?

Yeager: No‚ he's going to do this tape at home. He's going to bring it home with him.

Lowry: Don Stewart was against us being roommates.

Yeager: Oh‚ really?

Lowry: He want to the President‚ and he said that he didn't think three blacks should be roommates. And we said‚ “Don‚ it's not a matter of integrating the school.“ We just enjoyed each other. And we did. I think that's why we didn't have the feeling of isolation that other--because we were friends. We didn't have to deal with it psychologically‚ being segregated. I mean it was not a matter of three blacks being segregated. It was just three friends. But Donald was against that.

Yeager: What other blacks were at Grinnell? Who were they? Do you remember?

Lowry: Sure. I can name them. Herbie Hancock was one famous one. There was a guy named Henry McCullough‚ who is a nuclear scientist now; Ron Gault‚ who is Commissioner of Employment in New York City; Bill Lightfoot‚ who is a doctor; Everet White‚ who is now a doctor; Carol Williams‚ who is a housewife; who else? That's about it. Maybe a couple more at Grinnell‚ but Lowell Baker.

Yeager: That's a pretty accomplished group‚ there.

Lowry: Yeah‚ very accomplished group. Lester Roddy‚ a consultant on the west coast; Jim Payne‚ president of a consulting firm...“

Yeager: Who was the other one you named?

Lowry: Lester Roddy and Jim Payne. I just saw a list.

Yeager: Can you tell me a little bit about the interaction between the other black students.

Lowry: Oh‚ it was very good. We kidded a lot‚ but we were very supportive and very friendly. And those relationships have been maintained for twenty years.

Yeager: There was no CBS?

Lowry: No way--no.

Yeager: But Beth Turner had told me that black students interacted a lot.

Lowry: Oh yeah‚ they did. It was a natural grouping.

Yeager: How did it work? She said that you didn't see all ten of Grinnell's black students walking together down the street ever‚ But certainly there was some type of interaction.

Lowry: Oh‚ there was definitely camaraderie. We'd get together‚ and it was a very fluent kind of support system. I mean‚ that's the best way to describe it. You know‚ I saw Ron Gault and we'd kid about playing basketball and him not making the team. We kidded hard. We were hard kidders. But we'd laugh‚ and he'd say we couldn't dance. We were just very supportive. We were very close.

Yeager: At that time‚ then‚ most of the dating went on between that group?

Lowry: No. We eventually... Let's see. Most of us ended up with interracial couples. Allison married his white girlfriend. I dated... Well‚ I went back and forth. My sophomore and junior year I dated. I monopolized the two black girls on campus. There was one called Susie Brown‚ who I didn't mention‚ who is now a doctor‚ and Mickey Clark‚ who you might have heard of‚ and she's deceased. And I dated those two my sophomore and junior year. And then I married....went out with a town girl my senior year.

Yeager: Black or white?

Lowry: White. Susie Gustafson.

Yeager: Can you tell me. What was the reaction of the town at that period?

Lowry: Oh‚ God‚ they were going to castrate me! Seriously‚ I was forewarned by the townies‚ by the young kids who followed me in basketball. I got about three or four calls from young kids who said‚ “My uncle's coming to get you‚ Lowry

Yeager: Really? It was that bad?

Lowry: Oh‚ yeah.

Yeager: Can you tell me‚ how did you deal with that?

Lowry: Well‚ actually‚ it really just came out the spring of my senior year.

Yeager: So it wasn't a long period of time.

Lowry: No. Because I started dating her at Christmas in earnest‚ and that's when we started dating. So between December and then they started coming out in the spring. We would always have problems. I mean‚ Grinnell had problems with townies during the spring. And this particular spring was the spring of my senior year. And it came back. We talked to Burmos who was a professor. He was the Justice of the Peace. We just asked him ... There was a lot of mediating going back and forth. The gut never said anything. He was the same guy‚ who evidently‚ after I graduated‚ really took it out on the subsequent classes of blacks. It's Jim somebody. But he never ever said a word to me. But I knew about this. I knew about you know‚ the whole thing. But he never said it.

Yeager: Was this unusual? Were many black students dating townspeople?

Lowry: No. That was a unique thing. I mean the town basically tolerated whites and blacks dating‚ but I think the straw was Susie Gustafson‚ who was not only a townie‚ she was a blonde‚ blue-eyed homecoming queen.‚ And the combination of all that‚ but her parents are still my best friends. Her parents were just... Her parents are still good friends with me. My mother comes and visits the parents‚ and the parents were very courageous people. Once‚ we took a trip back to Chicago in my car‚ and she called after she got home ...

Yeager: She wanted to find out whether everything was all right?

Lowry: No. She just called and told them that we had arrived safely‚ and the telephone operator then picked up the phone and started calling all over town. And the father‚ little o1d‚ frail guy‚ went down there and talked to the guy who. was head of Iowa Bell and said that “I will sue if that ever happens again.“ It's a very unique thing. A very unique thing‚

Yeager: Can you tell me if there were any black families in Grinnell at that time?

Lowry: There‚ was one.

Yeager: That was the Lucas family?

Lowry: Yeah. They ran them out‚ that family. They ran them out. You should see them walking down the street. He was kind of a weird kid anyway.

Yeager: So there wasn't much interaction with that family?

Lowry: No.

Yeager: Because earlier... They'd been there a long time and earlier black students would eat with them.

Lowry: Is that right?

Yeager: Yeah. You didn't have any white roommates?

Lowry: I had college roommates. It was inter3-'°'S.lt.!i§?.g. I had a very good friend named John Groteluchen. Inevitably‚ we were roommates. We would room on the hall on the road.

Yeager: On the road?

Lowry: Played basketball. John is now vice-president at Carroll College. From Manning‚ Iowa.

Yeager: What was the reaction of white student to the presence of black students on campus?

Lowry: They loved us. In the first place‚ it was a very unique group of black students. It was pretty... How in the hell could you not like Jimmy Simmons. I mean the world likes Jimmy Simmons. How could you not like Allison? He was just bubbling and--I think that was much a part of it. I think the black students carried it. So‚ you know‚ in hindsight‚ Jimmy and I .... I don't know if Jimmy's hit on this‚ but‚ in hindsight‚ as we both look back‚ probably both of us gone through therapy‚ but we came in Francis Parker and Grinnell saying‚ “Oh‚ what a great thing that Grinnell's doing letting us get into this very prestigious school.“ But looking back in the later years say‚ “Hell‚ we did them more a favor than they did us.“ v1Je didn't feel it then‚ We definitely did not feel it. But I think that was true of all the black students. It was a very unique group.

Yeager: But the relationships with white students were not all superficial relationships? They weren't surface ...

Lowry: Oh‚ no. We had some very deep‚ deep relationships. Very strongly. I mean‚ I still have ...

Yeager: You were playing the role‚ but you also threw off the role in certain situations‚ right?

Lowry: Yeah.

Yeager: Did you perceive any college housing patterns with regard to black students? Did the college make an effort to house black students with blacks and whites with whites? Integrationist housing.

Lowry: There were so few. I mean‚ I could tell you almost the hall these guys were in.

Yeager: Did black students live with black students?

Lowry: No‚ Simmons and I were the only ones.

Yeager: You were the only ones.

Lowry: Yes. See‚ and I really think that's what happened. I mean‚ if you really want to know the truth. I really think that‚ and Jimmy and I insisted on it. Now‚ I don't know if it was planned or not‚ but Jimmy and I insisted on being roommates. And they put Allison in‚ but I din't think they realized that Allison was black. Because Allison looks like you. I mean‚ they just didn't know. But they never did that before or after‚ they never put two more blacks together.

Yeager: What was the reason for that? Just because of integration?

Lowry: I don't know. They just wanted to integrate us. They wanted to get us very exposed‚ us happy black people. I don't know. Ask Howard Bowen. I don't know.

Yeager: Now you're coming from a black neighborhood in Chicago...

Lowry: Yeah.

Yeager: ...and Jimmy Simmons is coming from the same area.

Lowry: Right.

Yeager: What-how was is-it was a lot different for you‚ coming to a predominately white environment.

Lowry: You mean here‚ in Grinnell?

Yeager: Yeah‚ Grinnell‚ as opposed to Chicago.

Lowry: No‚ Francis Parker... I mean‚ this was duck soup after Francis Parker. This was easy-Grinnell was easy‚ in terms of transition. I mean‚ all of us have our biases‚ and maybe that's my bias when I'm on the board now‚ looking back. But you know‚I mean when kids go through prep schools and day schools-I mean‚ Grinnell's very easy. The real problem for us‚ for Jimmy and myself‚ was eighth grade at Francis Parker. That was the trauma.

Yeager: What was in eighth grade at Francis Parker?

Lowry: Oh‚ we came their and I had a thick‚ thick brogue. I don't know if you know what a brogue is‚ it's a thick‚ thick ethnic accent. It was so thick‚ I mean‚ I was dawdling over my words. You couldn't understand what I was saying. And it was so thick that Francis Parker used to laugh at me‚ and they couldn't understand what the hell I was talking about. And so‚ after years of being exposed‚ I faced it and I talked like I talk now. So‚ when we came here‚ it was no big thing. It was very traumatic there. But‚ oh God‚ it was so traumatic.

Yeager: Now‚ your parents. Are your parents still alive today?

Lowry: Yes.

Yeager: When you started going to Francis Parker and you started eventually‚ to change your dialect. How were you received in your old neighborhood? Did you switch back and forth?

Lowry: Oh yeah. I was‚ still do‚ yeah. Sometime I didn't realize. I switched three times. I mean‚ if I'd be in Africa I'd be talking with a British clip. People tell me I do it. I don't even realize I do it.

Yeager: But you couldn't communicate if you didn't do that?

Lowry: Yes. It makes people feel easier.

Yeager: Now‚ from your recollection. Did most white students have previous experience with blacks?

Lowry: No. We were very unique. Well‚ remember‚ in those days‚ you had about fifty percent from Iowa. The rest of them came from Des Moines or Waterloo. They didn't...

Yeager: Did white students ever confront you and ask you about being black? Or was that a “no-no?“

Lowry: Oh yeah‚ they asked all kinds of silly questions.

Yeager: For instance?

Lowry: Oh‚ the classic is-back in those days‚ it was before the afro. So we used to wear our hair very close‚ but we'd wear a stocking cap. When we went walking around. That was the talk of the whole campus. What the hell has he got on his head? And the interesting thing-it's almost comic relief-is two little guys who idolized us started wearing stocking caps. One was from Boone‚ Iowa. It was funny.

Yeager: Was this the one who eventually took you-or went back with you to Chicago? Was this the one Jimmy talked about‚ you brought a few students back with you to Chicago?

Lowry: Yeah‚ we took a lot of them back.

Yeager: So you didn't have any problems with your identity then‚ going into a white environment?

Lowry: Oh‚ sure.

Yeager: You did have problems‚ then?

Lowry: Yeah‚ but it just wasn't as tough as Francis Parker. Sure‚ we had problems.

Yeager: How did you deal with it?

Lowry: We had... we were athletes. So we might feel a certain degree of insecurity in the classroom‚ but we were superior to everybody else on the athletic field. So we were big men on campus. So we never suffered overall an inferiority complex. And I think the one other thing which is such a profound thing that happened on campuses like this is that academically we were probably better than we were given credit. But at that time‚ a 'B' was for us just like an 'A'. The professors giving us B's and thought‚ “Oh‚ God‚ how these...black people can get B's.“ And I guess of the three‚ I had the highest grade average. But nobody ever though I was a great scholar. And I didn't think I was a great scholar‚ because they told me I wasn't a great scholar.

Yeager: They told you?

Lowry: Oh‚ yeah.

Yeager: Now‚ is this something that... Did they tell everyone that they were or they weren't‚ or was this...?

Lowry: It was a subtle thing. See‚ none of the stuff‚ even back in those days‚ was out and out blatant. It was just like “Oh‚ Jimmy‚ that was a great paper‚ just a fantastic paper‚“ and it was a 'B-'. You know‚ that kind of stuff. You feel good it was a brainwashing because you said‚ “Oh‚ God‚ you really thought highly of my because you gave me a B-.“

Yeager: It might not encourage you to work that much harder.

Lowry: Sure‚ you knew you'd never get A's‚ so you're‚ you know that's why... You know‚ it's a very fuzzy area when professors even now say that we never had black students who performed at a certain level‚ it's all a self-fulfilling prophecy. If you go in thinking that way‚ you're not going to give them any. Only now‚ Francis Parker's giving A's out now‚ probably‚ about thirty years‚ seriously.

Yeager: Now Francis Parker was a very integrated school?

Lowry: More so than Grinnell.

Yeager: So we talked about social interaction between whites and blacks ... What kind of extra-curricular activities were you involved in other than three sports?

Lowry: I was head of G-Honor G.

Yeager: What was that?

Lowry: Honor G.-they don't even have that now.

Yeager: Oh‚ Honor G. Yes they do. Isn't it when you have a certain amount of letters?

Lowry: Yes‚ letters-a letter. The first letter‚ you're automatically initiated into the Honor G society. to give us jackets and all that good stuff. They used

Yeager: That's not really big anymore.

Lowry: No‚ That was big stuff back then.

Yeager: Anything else?

Lowry: A couple plays‚ nothing very much‚ though. We just didn't have time.

Yeager: Did you feel discouraged from participation in any extracurricular activities because of race?

Lowry: Nope.

Yeager: Felt free to go into anything you wanted to go into?

Lowry: Anything.

Yeager: Many alums have suggested that Grinnell was an isolated and insulated community.

Lowry: That's true.

Yeager: Can you talk about a little bit?

Lowry: It was like an island. It was almost like the highway bordered an island.

Yeager: Did you have contact with the “real world?''

Lowry: Not unless ...go down to the barber shop‚ go down to McNally's and get some food ...they'd say “Hey‚ Lowry.“

Yeager: Were you aware of some of the activities taking place outside of Grinnell‚ some of the-you were talking a little bit about civil rights.

Lowry: Oh‚ you mean outside of Grinnell‚ Iowa.

Yeager: Outside of Grinnell‚ Iowa.

Lowry: Oh‚ hell‚ yes. No‚ I was just talking about when I was here. When we went back to Chicago‚ it was a different world.

Yeager: How did you deal with that-going back and forth?

Lowry: Great. It was great. I mean‚ we'd go back‚ and we'd have a very active social life during the summer. We'd go out and get drunk and chase women and have a great time. Jimmy Simmons and I worked for Pepsi Colas the whole time‚ and built out muscles-then we could take off and train for a couple weeks and then we could come back for early football. That's why Allison never got the inside rooms. He always got the outside room. But we had a great social life‚ back in Chicago.

Yeager: Now‚ Chicago had a lot more civil rights activities going on there...

Lowry: We were never really a part of it.

Yeager: You were never really aware or involved ...?

Lowry: I was aware. Hell‚ I was aware. But I wasn't ever involved. Probably scared. You know. But no‚ we weren't... we weren't really a part of it.

Yeager: A little bit before...

Lowry: Yea‚ it was a little bit before‚ I mean‚ it was really the early sixties‚ that they really took off‚ and then I was away out of the country.

Yeager: So it wasn't disinterest‚ but it was...?

Lowry: It hadn't manifested itself. I mean‚ King was not big in the fifties.

Yeager: I see‚ so you were just kind of following and seeing...

Lowry: Yeah‚ it was beginning to‚ you know‚ rise up.

Yeager: So how did you view other leaders-those leaders at the time? Were you supportive‚ or did you-you weren't sure they were doing the right thing? How did you perceive them? Did you think about that?

Lowry: It's a good question-I'm still thinking about it. It's the bane of my existence‚ I think. At the time‚ I thought then‚ and I think the same thing twenty years later‚ that they were very courageous people who were doing very courageous things‚ and because of their actions‚ I was going to benefit-or I benefitted. But I never thought for a day that they would win.

Yeager: That they would win?

Lowry: That the whole process-I saw it as a takeoff‚ you know‚ period in that-and I think that‚ that's one thing about writing a book about this‚ is that the fatal weakness of the civil rights movement‚ is that they couldn't go through stages. And that's why blacks in America right now are in very‚ very bad shape.

Yeager: What do you mean by stages?

Lowry: I'm saying the civil rights stage-let me deal with developing countries‚ to try and use an analogy. You take Ghandi in the civil rights-civil disobedience-that got them in the door‚ it got them independence from Britain. But if they just stayed at that level‚ without thinking in terms of developmental policies‚ they would all be beggers in Calcutta. You have to change‚ you know‚ and what worked for you then ain't going to work for you next thirty to forty years‚ 'cause you have a different set of problems. And I think we never developed. What you had were a lot of models that came out of the sixties‚ which were social workers‚ educators‚ social scientists in a lot of different ways‚ but this is a capitalistic society. And until we start building businesses and corporate leaders‚ then we would always be at the mercy of the people who felt morally guilty.

Yeager: Now‚ you started seeing that a little bit in Atlanta‚ now‚ right? More than in any other city‚ you find black business starting to build up.

Lowry: No‚ it's just the opposite. Well‚ you see‚ in Atlanta‚ not just now‚ Atlanta-my mother's sister's from Atlanta-and you saw black business prevail or succeed in Atlanta because they had no choice. Because there was no integration on any major scale. So therefore‚ the black community was forced to take care of its own needs: vis a vis insurance companies‚ vis a vis banks‚ savings and loans‚ housing‚ development-so you've built up this business class‚ and I think that's what you're going to see in society now.

Yeager: So you don't think there will be more of an integrated society?

Lowry: No‚ they'll be more segregated. Definitely. It'll be very interesting to see what happens. And I don't know if the whites or the blacks‚ certain blacks will be able to deal with it‚ but I don't think there's any choice.

Yeager: Were you influenced by any black authors at Grinnell? Did you read any black authors?

Lowry: Read anything I could get my hands on. Going through that era‚ I read every black book I could get my hands on.

Yeager: Why? Why was that so important?

Lowry: I wanted to know what was happening. It was scary. I mean‚ it was just like you saw these problems and we started wanting to get the answers to them. And I started in Grinnell‚ and then when I went away to the Peace Corps-I went to Africa pre-Peace Corps‚ and then after Peace Corps I had a lot of time to read. And that's all I would read. I read everybody... Lomax‚ Ken Clark‚ Malcolm X...

Yeager: Who did you most identify with?

Lowry: Malcolm.

Yeager: Now Malcolm died after you left Grinnell‚ wasn't it?

Lowry: After I left Grinnell‚ right.

Yeager: You never heard him speak‚ right? In person.

Lowry: No.

Yeager: Why were you affected by Malcolm X as opposed to Martin Luther King?

Lowry: Logic. I mean‚ my whole thing is logic. Not that it always works ... King was raised southern. Not bad or good‚ he was very southern. He had southern mannerisms and southern speech‚ and he had a southern way of looking at things. And even til today‚ I and others like me don't coalesce very well with southern leaders.

Yeager: Is it because of the religious differences?

Lowry: Cultural differences.

Yeager: Totally dure to cultural differences?

Lowry: Yeah‚ I mean‚ I think that there is a ...you heard me say it here‚ but I think over the next twenty years‚ you're going to see a change. You're going to see a change in the black leadership. And the first thirty years are going to be southern blacks who came up in the movement‚ who're going to be your leaders. The next thirty years are going to be your Grinnell‚ Swarthmore‚ Harvard wealthy leaders. Because‚ I think‚ this group‚ or my group can-are better able to deal with them-you‚ than Andy Young. Andy Young will never be able to deal one-on-one with whites. Culturally‚ he just can't do it. He might either-he goes to two extremes. Either he is going to be attacking you and challenging you in a far more hostile way for an Andy Young-type person‚ than I would ever do. But on the other hand‚ he will never be able to deal in the very subtle way which only comes from acculturation in a predominantly white environment.

Yeager: Malcolm X appealed to mostly lower industrial...

Lowry: Oh no‚ he didn't. He appealed to everybody. His logic was impeccable. 1I1he way it comes out-but I knew it then‚ most people didn't know it‚ but...Malcolm was tremendously smart and logical and all the rest‚ but Hailey wrote a lot of the books. I mean‚ it was a brilliant book‚ it was well written...

Yeager: Now‚ at Grinnell‚ what type of emphasis was made to the black experience in the classroom?

Lowry: Enlighten...Condescension.

Yeager: So it was discussed‚ but it wasn't accurate‚ in your opinion?

Lowry: ...no frame of reference. Who could dd it? I mean‚ Al Jones‚ Eddie Gilmour-they had their hearts in the right place‚ but...most of Grinnell now is basically European history and political experience‚ but there's a whole gap. When you think about it‚ very little is written in the academic perspective‚ other than the social service areas‚ about black experiences. It's very rough. I just wrote a 400-page report for commerce‚ going over a number of books that were written about black business in the last hundred years. You can count them on one hand.

Yeager: Were you involved in any black organizations or biracial organizations at this time when you were at Grinnell? Were you a member of NAACP...

Lowry: NAACP. I paid dues. I wasn't active.

Yeager: Why did you join that organization?

Lowry: Because it was the thing to do?

Yeager: Were your other two roommates members of NAACP?

Lowry: I'm sure.

Yeager: Not Urban League.

Lowry: Not at that time.

Yeager: What kinds of reactions were white students having at that time to early civil rights activites? Did it affect them? Were they interested at all?

Lowry: Not that much. In the fifties everything was up-we're going to help. But there was not the really strong commitment that I saw as a trustee in 1965‚ we just didn't have that. We didn't have Vietnam.

Yeager: You did have ROTC‚ though‚ right?

Lowry: Yes.

Yeager: And did you have-did you get out of that? Did you go through that? How did you get out of that?

Lowry: How did I get out of that? Maybe it was volunteer at the time. I think it was. It was volunteer.

Yeager: There was a Grinnell chapter of the NAACP. You were talking about this-you were involved in Chicago‚ not the Grinnell... Do you remember a Hampton exchange program?

Lowry: Hampton exchange? Probably earlier.

Yeager: There was no exchange program at that time with black colleges. Were you involved in International Club?

Lowry: No.

Yeager: But you went on in the Peace Corps and you went to Africa.

Okay. Name the most positive and the most negative personal experience you had at Grinnell.

Lowry: I've told you the most negative. To be threatened castration.

Yeager: That's pretty negative.

Lowry: Pretty negative. That's the bottom line.

Yeager: And what was the most positive? So you took that very seriously‚ the threat that was made to you in town?

Lowry: Yeah. I was scared. I was really scared. That's another thing is-you know‚ I never even thought about that‚ but I think even though we were integrating and things were basically good‚ we were always scared. Whereas now‚ I think we're going backwards‚ but I'm not scared. I just don't have a feeling of fear that I had in the fifties and sixties. I really had anxieties‚ strong anxieties about being black here at Grinnell. Most of it was under the surface‚ we would hide behind Grinnell and all that kind of stuff‚ but we were very‚ very sensitive to things that could happen to us. Like when I'd drive-it-wasn't-I didn't have any real experiences‚ but I was very nervous driving Susie Gustafson 1OO miles from Grinnell‚ Iowa to Chicago.

Yeager: Was it rural areas?

Lowry: We'd take the highways...Route 6...we were just nervous. Didn't know what the truckers would say... I think that with all of us you had that anxiety that was constant‚ that was with you almost every minute of the day.

Yeager: Did you relieve that anxiety through athletics? Or did you never relieve it?

Lowry: You never did. It's just-you never do. It's there‚ something you live with and I think that's part of one of the reasons we have more high blood pressure and heart attacks. It's a lot of stress.

Yeager: What was the most positive experience-I didn't hear that you had?

Lowry: It was winning the David Theopolis award for the most outstanding athlete. Well winning-it all came at the same time winning that award and getting the scholarship to go to Tanzania.

Yeager: Who had the most personal influence on your life as a student?

Lowry: Dr. Fletcher.

Yeager: Why?

Lowry: He just was a very polished person who perceived to have a sincere interest in me as a person‚ and it felt good‚ and he was an academic type. He cared for me as an academic-not an athlete.

Yeager: So you thought that that was an important part that wasn't recognized by many people that this man did recognize in you.

Lowry: I was a genius then‚ and I didn't really recognize it. I mean‚ I had-and I don't know if they told you this. I had a laundry service‚ I had washing machines‚ I had a flower service‚ and I used any time I wanted to make some money we would run a laundry service from door to door or we would make ROTC sandwiches-I kept money. Money was something I liked. I didn't have much as a kid‚ and I used to like making money. And not one professor ever told me I ought ot go to business school.

Yeager: So you were really entrepreneurial.

Lowry: I was entrepreneurial. Oh‚ yes.

Yeager: More than most kids‚ probably.

Lowry: Oh‚ yes. I always have been.

Yeager: And no one really encouraged that?

Lowry: No. Not one person.

Yeager: Now‚ who was the most influential author-did you have an influential author?

Lowry: That's a good question. I don't think so. Not any one.

Yeager: What about a student? Who influenced you as a student most? A student that you highly respected or that you learned a lot from ...

Lowry: Stewart‚ to a great extent. I was always proud of the fact that Stewart worked hard and made Dean's List. I took a lot of pride in the fact that Don Stewart became a scholar and made the Dean's List.

Yeager: But Don Stewart ...did he fit into your crowd?

Lowry: No. He never did.

Yeager: He was a little bit different.

Lowry: Right.

Yeager: He was kind of outside of...was he more friendly with Allison Davis?

Lowry: To a certain extent. We isolated him.

Yeager: You isolated him‚ or he isolated himself?

Lowry: We isolated him. It was both. Don is very-Don has always been very‚ very cognizant of what people looked at and perceived. And I think we were more loose. And‚ I mean‚ although we were guarded‚ we still hung out.

Yeager: And he didn't.

Lowry: No‚ he just-he was very focused‚ I think he did have a career objective and career plans‚ and he was working towards those.

Yeager: Now do you think that most of the other students \Vere similar to you or to Don‚ if you could categorize?

Lowry: We all were achievers‚ but I can't think of any of us who perceived ourselves as being academic achievers. We always knew we would be students‚ and pretty good students‚ and we would get through this place-none of us thought about flunking. And we'd go somewhere else because of Grinnell and because of ourselves. But we never aspired to be an expert or someone who's renowned in their field.

Yeager: But Don was ...

Lowry: I think Don did‚ yeah.

Yeager: So you did have long-lasting friendships and relation ships with Grinnellians‚ black and white.

Lowry: And professors.

Yeager: And professors. You're back as a trustee‚ so...

Lowry: No‚ I think that's why I was a trustee.

Yeager: As a result of those friendships was the reason you decided to come back to Grinnell?

Lowry: Or vice-versa. But I think that's the reason why they selected me to be a trustee. I think. I got them in three different ways: I was young enough‚ I was‚ at the time‚ working for a highly respectable consulting firm and I'd always maintained good relationships and I'd had the four years at Grinnell. So they thought I would be a good guinea pig to be the first black trustee.

Yeager: That's another area. You talked a little bit about playing the role. How did you feel? Did you feel like you there was tokenism? Did you fell like you were a token and everything?

Lowry: When's that?

Yeager: During this period. I mean...

Lowry: You knew you were.

Yeager: You were‚ you definitely were.

Lowry: Sure.

Yeager: How did you react to that?

Lowry: Like I said: we were grateful to be in here‚ so you played the role.

Yeager: But you had resentment in a certain way?

Lowry: Oh‚ yeah‚ it's resentment you still carry with you.

Yeager: Which is...

Lowry: There are a lot of things I'm bitter about. When I look back‚ although‚ the best way of putting it during the four years it wasn't catastrophic. I think that the difference between our group and the later groups is that you had a lot of people dealing with what was happening and playing it back‚ you couldn't escape the reality‚ you know‚ of being black in this environment. I think in the sixties and in the late fifties‚ people were trying to play down the blackness and talking about integration and because of the everybody was on a high‚ every body was trying to be nice‚ you didn't let certain feelings surface. And twenty years later‚ when you look back-I mean‚ like the business thing. I get better. I really get bitter. Or professors who felt they were doing me a favor or the overall concept of me as a non-student. And it took me until I got to Harvard when I out-performed everybody in my class that I finally said‚ “Hey‚ I am very smart.“ But it was all that brainwashing. It took me until 1972 to get rid of that brainwashing.

Yeager: So you're very bitter about that‚ then.

Lowry: Very bitter.

Yeager: We talked a little bit about the town. I was wondering the reaction in town-was it a positive one?

Lowry: Basically.

Yeager: Now‚ Jim Simmons had mentioned a very funny story to me about the barber‚ that it was the first time that they had cut black hair. People were not experienced at all with the blacks? But the experience was not a negative one?

Lowry: Oh‚ yeah‚ they didn't know what to do. Well‚ no‚ that's the interesting thing. I mean‚ in the sense that during the time we were there we would walk into that barber shop and those barbers would treat us like kings‚ but we later found out that one of the barbers‚ or maybe two of the barbers‚ as soon as we left‚ would tell nigger jokes. And the only way I knew and started to deal with it was after I graduated I looked back on the son of that barber and I realized when he was at Cornell‚ he was part of a group that gave us a hard time as blacks. And I said‚ “Wait a minute‚ how can he be the barber's son.“ But they never surfaced. And I think that that was a great protection that JiIThuY and I had‚ that we were bigger than life. So they really didn't mess with us.

Yeager: You talk about fear...a lot of people‚ you felt‚ were talking about you behind your back‚ but nothing ever surfaced?

Lowry: It really never did. On one hand we knew that there was potential danger-not physical-except for that one time‚ I never really felt that strong‚ but you knew something was always lurking there.

Yeager: You never were refused service‚ you never were not cooperated with in to m?

Lowry: What's the one down on the highway? We had a little problem down there once.

Yeager: At a store?

Lowry: No‚ it was a bar. Next to the pizza place‚ down around there. Used to be a restaurant down there. Pizza Hut. It's not Pizza Hut‚ but it used to be a little‚ small restaurant... The truckers-that was a bad place because there were a lot of truckers.

Yeager: So generally‚ the town experience wasn't really a negative then?

Lowry: Not really.

Yeager: Did you go into town very often?

Lowry: Sure.

Yeager: Did you know any black alumni-well‚ blacks who had gone to Grinnell in the past?

Lowry: Well‚ I mean‚ when we came we met some and so there were ‚recent graduates. Alphanette White was one‚ and then Dibble we had heard about.

Yeager: Not farther back?

Lowry: No.

Yeager: You didn't get the chance to meet some of the real old timers‚ then?

Lowry: They had some real old-timers?

Yeager: Oh‚ yeah.

Lowry: How old?

Yeager: Ah‚ well‚ black students go back to the 1870's.

Lowry: No kidding?

Yeager: Like Otis Redmon or Clifton Lamb‚ or some people that went to school in the twenties-Gordon Kitchen-Gordon Kitchen's still living.

Lowry: No kidding.

Yeager: He's a T.V. executive.

Lowry: You ought to give me a list of them. I'd love talking to them.

Yeager: ...The earlier black students. You didn't have any knowledge of any of those students. Last two questions here. Were you happy at Grinnell?

Lowry: Yes.

Yeager: Very happy.

Lowry: Yes.

Yeager: Despite...

Lowry: I of a lot was more very happy. Let's put it like this: pleasant experiences from all facets I had a hell of this place than I had negative. I talk about the negative. When I think back I think about you know‚ a lot of very‚ very enjoyable experiences with-like Mrs. Nollen‚ you know‚ we got to be good buddies. Pfitsch and his crazy self‚and Emily Pfitsch and the Gustafsons and Kleinschmidts and the Walkers. I mean I just have a lot of fond memories‚ you know.

Yeager: Can you elaborate on the activities once leaving Grinnell? Your graduate work ....

Lowry: Grinnell sent me to Tanzania‚ worst goddam thing I ever had.

Yeager: How did you go to Tanzania-what program was this?

Lowry: It was called the fifth year abroad. I was the first non-Christian to go. They used to give it to _all the philosophy majors because they thought they could save souls better than anybody else. In my year they sent five. Usually it was one person‚ and they sent five. I went to Tanzania and I didn't know what the hell I was getting into. And I didn't have any real plans‚ so I went. It's just like somebody goes into the army. God‚ it was so hard. It 'Nas so hard. Here I was‚ a guy who's been-had this beautiful girl and I was a basketball star and all that kind of stuff and all of the sudden on that island with no money and no girls. Had to be a little crazy... and of course‚ there were suffering black people-I had to feel guilty. I was counting the days. I was counting the days. Those were a hard 365 days.

Yeager: It wasn't a good...?

Lowry: It was a good learning experience‚ excellent learning experience. Excellent. I mean‚ I learned about so much‚ about life‚ about Africa‚ Europe-it was a great experience.

Yeager: What was the program? What did you actually do?

Lowry: Nothing‚ I mean‚ I was supposed to teach‚ but then the British didn't think I was qualified with a Grinnell degree.

Yeager: Oh really? Because you were black?

Lowry: No‚ because I had a Grinnell degree. They were Oxford trained people with Masters'. Maybe Harvard‚ maybe.

Yeager: If you didn't teach‚ what aid you do?

Lowry: Yeah‚ I taught-tutorials. You know‚ I had my ovm tutorial class‚ and every now and then I'd fill in for the teachers.

Yeager: So most of the time you were ...

Lowry: I read books.

Yeager: You read books all the time.

Lowry: Yeah‚ hangin' out in the city-hung out with the students.

Yeager: How was the experience different for you and what- being black in an African country?

Lowry: It was great-they loved me.

Yeager: How did you respond to that?

Lowry: I loved it.

Yeager: You loved it?

Lowry: Yeah.

Yeager: So you thought it was a valuable experience?

Lowry: Oh yeah‚ I used to swinging‚ I used to go dancing with and right now‚ my friends are now Prime Ministers‚ secretaries- my students.

Yeager: Is the Prime Minister of Tanzania someone that you know?

Lowry: Oh yeah.

Yeager: What was his name?

Lowry: Well the Prime minister right now is Musuya‚ but I met Julius Nyerere when he was President. I lived there twice. I went back in '72 with McKinsey‚ and lived in Tanzania.

Yeager: Why did you do that?

Lowry: That's a good question. It was dumb. I mean‚ it was really dumb. Well‚ I always thought-I said‚ “Well‚ hell‚“ back in those days I was poor‚ you know-well‚ I went back with McKinsey and I was making a lot of money and I was married. So I said‚ being married and having a lot of money‚ it would be a different experience. And it was. I mean‚ it really was different. But it was still boring‚ I mean‚ I'm American. I like everything like everybody else. Once again‚ it was a good experience‚ it gave me a chance to save some money.

Yeager: Can you tell me something about your work experiences ... once you got back from Tanzania?

Lowry: Peace Corps recruited me‚ then I became an Outward Bound instructor in Puerto Rico‚ and helping cross-cultural training. And then I met Bobby Kennedy-no‚ wait a minute‚ no. After that I went to University of Pittsburgh and got a degree in International Economics.

Yeager: M.A. or Ph.D?

Lowry: I got what they called an M.P.I.A.-iVIaster of Public and International Affairs. And then I went overseas to Peru and was an Associate Peace Corps Director. And then I met Bobby Kennedy and he invited me to go back to New York.

Yeager: You met Bobby Kennedy where?

Lowry: In Peru. He was on one of the South American trips. I was translating for him.

Yeager: And so you went from-that connection with Bobby Kennedy brought you where?

Lowry: To Bedford-Stuyvesant in New York.

Yeager: What is that?

Lowry: It was a-it was Bobby Kennedy's answer to the poverty program. He thought Johnson was wrong. He was also running against Johnson. For all intents and purposes. And he wanted to have an alternative program‚ using private capital to change the ghetto. And it was a bust. It gets more publicity than everything else‚ But when you're talking about impact something like Harlem or Bedford-Stuyvesant. Bedford-Stuyvesant restoration.

Yeager: What did you do there?

Lowry: I was Assistant to the President. And I ran about three or four different programs.

Yeager: So you were involved in administration at that point?

Lowry: Yeah. But I did a lot of street work. I was out on the block dealing with junkies-did everything.

Yeager: Was that a completely different experience for you?

Lowry: Yeah. Coming from Peace Corps. Because that was my first real professional experience working with blacks. And working for a black person.

Yeager: The president of it was black‚ I take it?

Lowry: Yeah. He was here ...

Yeager: What was his name?

Lowry: Franklin Thomas. And then when Bobby Kennedy was shot‚ just-my whole life just kind of changed. To me‚ that ended the sixties. It ended a whole era. And I basically retreated for seven years.

Yeager: You retreated into ...

Lowry: Corporate America.

Yeager: That's an interesting place to retreat.

Lowry: It was a great place to retreat.

Yeager: Why corporate America?

Lowry: I wanted to deal with a lot of people. I was with a consulting firm‚ and it was a very prestigious consulting firm‚ and they didn't bug you.

Yeager: What was the name of this firm?

Lowry: McKinsey and Company. They did not bug you. Everything was first class‚ you flew first class ...a lot of Harvard‚ Yale types. And I was ready for them; by that time I had the experience.

Yeager: Now you were disillusioned with social work?

Lowry: Yeah‚ Still am. I'm not disillusioned‚ I'm disillusioned for myself.

Yeager: So your occupation now is a consultant?

Lowry: On my own.

Yeager: You're on your own‚ now‚ you've moved off working with the consulting firm to opening up your ovm. How many years in these different things w~re.you involved?

Lowry: Looking back‚ I've had my firm six years‚ I was in Bedford-Stuyvesant for a year and a half‚ I was in the Peace Corps for two years‚ Graduate school two years‚ and then Peace Corps before that a year‚ Tanzania one year‚ and then Grinnell.

Yeager: Were you involved in anything related to the church in Grinnell?

Lawry: No. Went to chapel maybe six times.

Yeager: What kind of impact did Grinnell have on you life socially?

Lawry: Profound.

Yeager: It didn't bring you out of a shell because you never were in one‚ so ...you didn't marry anyone from Grinnell.

Lowry: No. It was very positive. I think I'm-now I would border on being arrogant‚ you know‚ and I think Grinnell‚ Francis Parker‚ McKinsey‚ Harvard‚ or all these things kind of added to my sense of security and confidence. Grinnell was very important.

Yeager: When were you at Harvard? You didn't mention that.

Lowry: Francis Parker-not Francis Parker-McKinsey sent me to the Harvard business school‚ Executive Program. For five months. So I stayed there for five months‚ the whole time with McKinsey‚ which was for seven years. That's pretty much all I have to say.

I think my whole thing-one thing with Grinnell‚ and I -think this transcends race‚ is that Grinnell is a great place for a learning experience. And I don't know if it's a place where a liberal arts college should do this‚ but I think the biggest problem I had with Grinnell‚ looking back‚ is that wasn't realistic in terms of what life is all about‚ but‚ more importantly‚ how do you solve problems. It is not a very good problem-solving place. And I'll even tell you something now‚ I mean‚ professors per se‚ are not effective problem solvers‚ per se. Professors at Grinnell are worse because they are this little cocoon and they make their own rules. I shouldn't even be biasing you this way. But they don't know what the real world's all about‚ and I think it's a disadvantage to me and because they are gods and goddesses. But they're so naive‚ and so ill-equipped to deal with the real world. So therefore in dealing with me and dealing with you‚ they' re giving us direction that is in many ways phony. I mean-I'll give you a case in point: the professor‚ the head of the faculty came to a group today of trustees‚ 85 percent of whom are business people‚ anybody who came to my office or their offices and would read verbatim a ten-page paper‚ we'd throw them out. And I'm sure it never dawned on him to even consider was this the appropriate thing to do. He's a professor‚ that's what he feels comfortable doing and he did it.

Yeager: He just didn't reach the business in you at all.

Lowry: We turned off. We just turned him off. Now if he doesn't even know we turned him off‚ because he's insensitive‚ 'cause he's God. That's what he feels comfortable with. The only bad thing is‚ he dictates the rules. So he is dictating rules and saying‚ “Look‚ this is what you ought to do.“ It ain't real. That's why we always like students better than professors. We do. They're better equipped. They're more able to relate to us than professors. Professors can't change‚ they're too old...

Yeager: You are going out into the world from Grinnell after being exposed to people who are ill-equipped. Did you have a difficult time?

Lowry: That's what I'm saying. I was ill-equipped. Oh‚ God‚ totally. It took me fifteen years to recover. I'll forewarn you. I think this is a different era. I think your era is different from my era. But that was all Hollywood and popcorn and American Bandstand. That ain't they way the world was. I mean‚ it's not so much the big things‚ you know‚ it's how do you deal with the boss‚ how do you deal with getting money-we weren't prepared for it. They didn't prepare us.

Yeager: Thank you.

Lowry: Sure.

- Title:

- Oral history interview with James Lowry, class of 1961, conducted by Stuart Yeager.

- Creator:

- Yeager, Stuart

- Date Created:

- 1961

- Description:

- An oral history interview with James Lowry. Lowry is a member of the class of 1931. Two original parts merged to one. Recorded on September 12, 1981.

- Subjects:

- Black Experience at Grinnell College Lucas family Peace Corps Athletics

- People:

- Lowry, James Yeager, Stuart Davis, Allison Simmons, James Gustafson, Susie Nyerere, Julius

- Location:

- Grinnell, IA, Chicago, IL, Tanzania

- Source:

- Grinnell College

- Object ID:

- dg_1724957066

- Type:

- Audio Recording

- Format:

- mp3

- Preferred Citation:

- "Oral history interview with James Lowry, class of 1961, conducted by Stuart Yeager.", The Black Experience at Grinnell College Through Collected Oral History and Documents, 1863–1954, Grinnell College Libraries

- Reference Link:

- https://yeager-collection.grinnell.edu/items/dg_1724957066.html

- Rights:

- Copyright to this work is held by the author(s), in accordance with United States copyright law (USC 17). Readers of this work have certain rights as defined by the law, including but not limited to fair use (17 USC 107 et seq.).